Tirohanga Whānui | Overview

The New Zealand Council of Christian Social Services (NZCCSS) welcomes the opportunity to provide feedback on the repeal of section 7AA of the Oranga Tamariki Act 1989. We affirm the government’s efforts to improve Oranga Tamariki outcomes regarding the safety, wellbeing and stability of care placements for tamariki. However, the experience of our membership and the information available indicates that the issues occurring in the Oranga Tamariki system relate to the implementation and resourcing of policy, rather than the legislation itself. We therefore express concern at the risk this repeal poses to the rights of tamariki Māori, and the positive gains achieved in the care ecosystem for tamariki Māori, because of section 7AA. We urge the government to prioritise evidence over ideology and consider alternative measures that hold greater promise of achieving this commendable objective.

Kaupapa | Purpose

The purpose of this submission and the main points.

We strongly recommend that the government address the following considerations:

1. Upholding the rights of tamariki and rangatahi Māori

2. Upholding a commitment te Tiriti

3. Lack of evidence-base to support the repeal

4. Urgency of decision-making

5. Strengthening the paramountcy principle

6. Supporting consistency in decision-making across the care and protection and Family Court system

7. Recognising the intrinsic nature of the mana tamaiti principles to the wellbeing of tamariki and rangatahi Māori

8. Loss of trust that has been established between government and iwi

9. The loss of the legislative basis for strategic partnerships

10. Potential loss of reporting and impact on oversight of the system

11. The intergenerational impact of policy swings

12. Adequate investment to support family preservation approaches

13. Assumptions about harm to children may fail to adequately recognise where harm continues to occur

14. Clarification of intent and implications on practice

Horopaki | Context

NZCCSS supports the paramountcy of children and young people’s wellbeing and best interests, which includes their protection from harm, as the primary consideration with regards to any decision or action taken under the Oranga Tamariki Act 1989. This objective is clearly articulated in the Act’s purposes (section 4A) and principles (sections 5 & 13). The driver for repealing section 7AA is a concern that the objectives it contains have been prioritised over the paramountcy of children’s safety and wellbeing in decision-making.

We hold the following concerns regarding this legislative change:

1. A repeal of section 7AA conflicts with children’s rights

Belonging is an intrinsic part of wellbeing, regardless of age or stage. Consequently, a truly holistic, Aotearoa-centric approach to children and young people’s wellbeing cannot be achieved in the absence of regard to mana tamaiti (tamariki) and the whakapapa of Māori children and young persons and the whanaungatanga responsibilities of their whānau, hapū, and iwi. These rights are upheld by te Tiriti o Waitangi, and in a range of other relevant protective mechanisms for children and young people such as the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), and the Child & Youth Wellbeing Strategy.

This repeal conflicts with these rights in removing the government’s practical commitment to te Tiriti and the rights of tamariki Māori contained within that. It also infringes on children’s rights to non-discrimination, identity, culture, development, and the right to have a voice and participate in decisions that affect them.

We refer to the join submission produced by Child Rights Alliance New Zealand which NZCCSS has endorsed, and which describes this impact of this repeal on children’s rights in greater detail.

2. Section 7AA realises government’s commitment to te Tiriti

NZCCSS affirms the honouring of te Tiriti in all matters concerning tino rangatiratanga of taonga. Section 7AA gives effect to the Articles of te Tiriti, legislating a practical commitment to upholding children’s rights and accountability for reducing disparities within the care and protection system.

While the Act as it currently stands leaves much to be desired for Māori in terms of true partnership and rangatiratanga over kāinga (Article 2) and reducing inequities (Article 3), the provisions contained in section 7AA create a legislative basis for partnership. Section 7AA provides accountability for realising the principles also contained in sections 5 and 13 of the Act, such as providing early intervention, preventative support to whānau, the identification of placements within the child’s iwi, and the maintenance of cultural connections. We observe from 7AA reporting that while still disproportionately represented in the system, there has been a positive reduction in the number of Māori tamariki and young people entering care in recent years.

As with any legislation, the Oranga Tamariki Act 1989 is designed to be interpreted in full. Section 7AA also places obligations on Oranga Tamariki to ensure its practices have regard for mana tamaiti, whakapapa and whanaungatanga. The mana tamaiti provisions contained in s7AA(2)b that raise concern for the Minister also exist in the purposes of the Act (sections 5 and 13), which guide all decision-making regarding care and protection. According to Williams et al. (2019), these purposes “provide a reference point to frame the obligation in section 7AA(2)” (p.9).

Within the context of social work practice, the mana tamaiti objectives guide how section 7AA is applied in working alongside tamariki and whānau. Rather than identifying new priorities that suggest cultural factors take priority over safety, these objectives, such as the involvement of tamariki, whānau, hapu and iwi in decision-making, and the preference for placing tamariki within their whānau, hapu or iwi, again reflect the principles for decision-making set out in sections 5 and 13 of the Act.

Our concern is that rather than removing the relevance of these principles in decision-making regarding the care of tamariki Māori, a repeal of section 7AA removes accountability for Oranga Tamariki’s actions. We view the loss of this accountability as being significantly detrimental to enactment of te Tiriti, to the rights of tamariki Māori, and to our ability to hold government to its commitment to addressing longstanding and well-evidenced disparities in our system. We refer to reports such as He Pāharakeke, He Rito Whakakīkīnga Whāruarua (Waitangi Tribunal, 2021), Hipokingia ki te Kahu Aroha Hipokingia ki te Katoa (Ministerial Advisory Board, 2021), He Take Kōhukihuki (Ombudsman, 2020) and Te Pūao-te-Ata-Tū (Ministerial Advisory Committee on a Māori Perspective for the Ministry of Social Development, 1988), which indicate systemic racism and a failure to uphold te Tiriti within the care and protection system.

This repeal also erodes progress we have made in addressing this fundamental challenge within our care and protection system, as described by the Ministerial Advisory Committee in Te Pūao-te-Ata-Tū (1988):

At the heart of the issue is a profound misunderstanding or ignorance of the place of the child in Māori society and its relationship with whanau, hapu, iwi structures. (p.7)

We urge the government to maintain its commitment to the Articles of te Tiriti, given effect through section 7AA.

3. There is lack of evidence to support the repeal: both a lack of robust evidence to suggest that section 7AA has caused poor decision-making, and a lack of evidence to suggest that a repeal will achieve the desired outcomes.

We are concerned by the lack of evidence base for the repeal, noting that it is clear from the Cabinet Paper and Regulatory Impact Statement that there is no robust evidence to support the claims that section 7AA has caused poor decision-making, or that the repeal will achieve the desired change in practice. In contrast, the Oranga Tamariki Section 7AA 2023 report indicates that the agency is “making incremental progress on improving outcomes and reducing disparities for tamariki and rangatahi” (p. 1). The report also shows that since 2019 there has been a noticeable decrease in the overall population of children in care, “driven by a decrease in the number of tamariki Māori in care” (p.42).

The Regulatory Impact Statement highlights that poor care decisions highlighted by the Minister derive from practice, not legislation. Issues referenced in the Cabinet paper of reverse uplifts, and children being forced to visit whānau in conflict with their best interests, were found to have arisen from issues of poor practice. Increased guidance and consistency in care and protection processes, service delivery and decision-making are needed to address this.

Without an adequate basis for legislative change, we urge the government to consider how improvements to practice could be achieved that are more likely to address the Minister’s concerns.

4. Practice issues must be addressed across the system

NZCCSS does not support the practice of “reverse uplifts” referenced by the Minister but suggests that the issues of practice that have underpinned these decisions, and others that may be of concern to the Minister are in fact widespread issues within the system and do not apply to tamariki Māori alone.

Our membership’s experience with Oranga Tamariki indicates that transitions often do not occur well or safely for tamariki. Drivers for this are thought to include inconsistency in practice, the loss of institutional knowledge and relational capital that occurs with high staff turnover, and lack of investment in resourcing Oranga Tamariki well. As a result, children, families, whānau and caregivers are not well supported to ensure that transitions can occur as appropriate for the child, and at a pace that is child centred. This means that children may remain in, be removed from, or moved into their home or placements without sufficient consideration for their wellbeing and the ability for those around them to care for them effectively.

We suggest that practice issues must be addressed more broadly across the system to ensure that all care decisions are appropriate and appropriately paced.

5. Urgency of decision-making

We are also concerned by the urgency with which this legislation has progressed. The pace required by the Minister has limited the ability for consultation, detailed analysis regarding non-regulatory alternatives, and adequate consideration of the implications of the repeal.

We expect that the timing of any repeal would have given consideration for:

- Periodic review of Section 7AA due in 2025

- Review of the mana tamaiti objectives as suggested in the Section 7AA 2023 report: “Now is the time to revisit the mana tamaiti objectives as they need to align with the future vision of Oranga Tamariki” (p.30).

- Findings of the Royal Commission into Abuse in Care are due to be released later this year. These findings will offer valuable insight into how our care and protection system could be improved to better protect tamariki.

- Acknowledgement of the expected five-year period it would take to transition to the intended Oranga Tamariki system and legislation (such as 7AA). We are only now just approaching five years since section 7AA was introduced in 2019 (Williams et al., 2019, p.7).

It is concerning that a coalition government focused on evidence-based approaches and return on investment is seeking to advance legislative change in the absence of a robust evidence base and without consideration for relevant review timeframes. Failing to incorporate the recommendations of the Royal Commission into Abuse in Care is viewed as a blatant disregard for the experience and insight of those who have suffered within our care system and raises questions as to how genuine the government is in its desire to see improved outcomes for tamariki.

Given that it is difficult to identify a conflict within the legislation itself, we suggest that the government’s focus shift to supporting practice and strengthening guidance regarding interpretation of the paramountcy and other principles contained within the Act.

6. Greater clarification of how children’s safety and wellbeing should be determined is needed, due to inconsistency in decision-making across the care and protection and Family Court system.

According to the Regulatory Impact Statement, the repeal of section 7AA seeks to “reprioritise the safety and well-being of children and young people in care arrangements” (p.6). However, as it currently stands, the Act’s prioritisation of the principles that guide wellbeing and best interests is unclear. It is evident that those making decisions for tamariki have struggled with a lack of clarity in how the paramountcy principle and the principles contained in other parts of the Act should be balanced. Keddell & Wilkins (2022) found that decision-making in the care and protection context was variable, due to influences and constraints that may include organisational context, availability of resources and demand, organisational culture, managerial preferences, patterns that are perceived to typically indicate risk and response, and national policy approaches which shape attitudes, reasoning and resourcing of care and protection. The authors go on to suggest that a fundamental base is needed to ensure consistency of decision-making:

While it is challenging to balance competing principles in response to diverse circumstances, there should be a priori a basic level of consistency, irrespective of decision-maker, ethnicity, geography (at least within the same country) and socioeconomic circumstances (p 2).

Our membership speaks to the inconsistency of decision-making observed across the Oranga Tamariki system driven by a lack of guidance and support associated with practice shifts, loss of institutional knowledge due to staff turnover, and a lack of adequate resourcing. We suggest that addressing these issues offers greater promise of the government improving the safety and stability of children in care arrangements than the proposed legislative change.

Because section 7AA refers to the duties of the Chief Executive of Oranga Tamariki, this repeal appears to have focused on Oranga Tamariki as an agency. However, a 2022 report by Te Puna Rangahau o te Wai Ariki | Aotearoa New Zealand Centre for Indigenous Peoples and the Law, highlights the responsibility of those within the Family Court system in determining wellbeing and best interests, and the lack of clarity that exists with regards to how this should be determined.

“There are currently inconsistencies in how the best interests of tamariki Māori are determined by Courts. While these inconsistencies mainly arise because the law is unclear and does not provide a distinct test for determining the best interests of tamariki Māori, another key issue is that often the judges who are making these determinations do not have knowledge of tikanga Māori and te ao Māori or fail to seek the relevant expertise to assist their decision-making on these matters.” (p.3).

The report identified that, when making best interest determinations for tamariki Māori, judges had differing views on 1) how to balance te ao Māori principles with the paramountcy principle, 2) how much weight to place on te ao Māori principles, and 3) what information was required by the Court from Oranga Tamariki, or other professionals, in relation to te ao Māori principles before a determination could be made. This led to varying efforts by social workers to engage with whānau or explore potential placements within a child’s whānau/hapu/iwi, and inconsistencies in the extent to which the Family Court required that these efforts be made.

We suggest that improvements be made to increase the consistency of decision-making regarding children’s best interests.

7. Clarity about how wellbeing is defined, and by whom, is also needed to ensure decisions adequately represent the mana tamaiti principles being intrinsic to wellbeing for tamariki Māori.

At the heart of these challenges is the perception that the protection of culture connections and cultural safety can be viewed as being just one component of wellbeing, rather than fundamental to it, and that this component may pose a risk to children’s protection from harm. This conflicts with Māori understandings of wellbeing, which are framed through the collective, not the individual, and consider the concepts of whakapapa and whanaungatanga as essential to a child’s wellbeing and safety.

The Te Puna Rangahau o te Wai Ariki | Aotearoa New Zealand Centre for Indigenous Peoples and the Law report referenced above recommends that the care and protection system be transformed to “recognise the authority of Māori to decide what is in the best interests of tamariki Māori and that tamariki Māori should always remain in the care of their whānau, hapū or iwi”. It also recommends that legislation be amended to “clearly prescribe how the best interests of tamariki Māori are to be determined and what procedures the Court must follow, particularly in relation what standard of evidence must be provided to the Court, what assistance the Court must seek to aid its determination and in what circumstances it will be prevented from making a decision until further information is provided” (p.19)

This is reflected in earlier commentary on the establishment of Oranga Tamariki, highlighting both the opportunity section 7AA offered to establish Kaupapa Māori approaches to measuring and reducing disparity, and the potential risks associated with interpretation of the mana tamariti objectives:

“There are other significant reforms that the 2017 Act details that have been inserted into the reformed 1989 Act and will come into effect in July 2019. Importantly, these include introducing new kupu Māori into the justice system such as mana tamaiti, whakapapa and whanaungatanga. This has potential benefits and risks. On one hand, it arguably puts kupu and tikanga Māori at the heart of the new provisions and directs decision-makers to ensure they are taken into account. On the other hand, it risks kupu and tikanga Māori being misinterpreted and diluted from their true meaning. (Williams et al., 2019, p.8).

We are concerned that a lack of clarity regarding best interests determinations under the Act is contributing to issues of practice, which will not be resolved through repealing section 7AA. We suggest that greater efforts be made to guide decision making for social workers and those in the Family Court, shaped by culturally appropriate understanding of wellbeing.

NZCCSS supports greater consistency in the implementation of the Oranga Tamariki Act, recognising that the mana tamaiti principles are fundamental to the wellbeing and best interests of tamariki Māori.

8. If legislative change is desired, strengthening the paramountcy principle, and children’s safety, in legislation would be more effective than repealing section 7AA.

If the purpose of the repeal is to ensure that the safety of children is prioritised over cultural factors, and legislative change is desired, we suggest that this could be better achieved through strengthening the paramountcy principle within in the Act while retaining section 7AA.

This could be achieved in the principles of the Act through inclusion of an additional clause, or as suggested by Dr Luke Fitzmaurice-Brown’s (Te Henga Waka | Victoria University of Wellington), the paramountcy principle could be reiterated in section 7AA as an alternative approach to the repeal.

Amendments could also provide greater clarification of how the wellbeing and best interests of the child should be determined, as discussed further below.

Given that section 7AA is intended to be read in conjunction with the overarching principles of the Act, we don’t believe amendment is necessary but suggest it as a preferred option to removing section 7AA entirely.

9. Concern regarding the loss of the legislative basis for strategic partnerships, shared outcomes and accountability and reporting.

We are concerned that despite the Minister’s claims that existing partnerships will continue, the loss of section 7AA will mean that there is no legislative basis for the current or future governments to maintain or establish existing or new partnerships with iwi.

The presence of section 7AA and the establishment of strategic partnerships with iwi has enabled the development of a shared vision, outcomes and accountability.

Our section 7AA vision is that ‘no tamaiti Māori will need state care’ – a vision that provides a significant and worthy challenge. A vision that has a rich history and whakapapa behind it. Most importantly it is a vision that is shared and strongly supported by our iwi and Māori partners. (Oranga Tamariki, 2020, p. 5).

We suggest that this is a far stronger position to be working from than that of government alone, and there is no doubt that a repeal will be interpreted as diminishing the value of this shared approach in achieving improved outcomes for tamariki and rangatahi. We believe this poses a risk to the safety and wellbeing of tamariki.

We are also concerned at the potential loss of innovation that will accompany this shift. Partnerships with iwi create opportunity for innovation in a sector where innovation is scarce, and poorly supported. Such innovation provides valuable insights into where greater impact can be achieved and how those insights can be leveraged across the sector.

Unnecessary and unfounded removal of the clauses of 7AA that relate to strategic partnerships will have an impact on the effectiveness of existing partnerships and their outcomes and poses a risk of harm to tamariki and rangatahi. We urge the government to retain the legislative basis for this approach.

10. Concern regarding the loss of trust that has been established between government and iwi

Repealing section 7AA and removing the legislative provision for strategic partnerships between Oranga Tamariki and iwi/Māori is a failure to acknowledge the past injustices and trauma inflicted by our care and protection system on tamariki and whānau Māori, and the journey towards healing and collaborative kaitiakitanga that section 7AA has fostered. We acknowledge the significant relational trust that has been formed via the existing partnerships, and the practical implications of this trust in improving outcomes for tamariki and rangatahi Māori.

The evidence now before us indicates that the relationships established under section 7AA have played an important role in strengthening trust and relationships between Oranga Tamariki and Māori. Officials go so far as to say the relationships established under section 7AA have been pivotal. We agree entirely with officials’ analysis that a full repeal will diminish confidence in trust in Oranga Tamariki in the communities for whom sustaining trust is most critical. Constructive engagement with such communities through connected iwi and Māori providers is a common-sense approach and one that ought not to be undermined by an arbitrary appeal of the provision under which a number of existing arrangements are in place (Waitangi Tribunal, 2024, p.16).

It is clear from the response from iwi that the suggestion of removing section 7AA has already affected this trust, eroding valuable relational capital. This has been further exacerbated by the failure of the Minister to engage in Waitangi Tribunal summons. Such a change is layered in the experience of the past, and fuels disillusionment that government will maintain shared vision, collaboration and a genuine commitment to seeing the Articles of te Tiriti realised.

11. Concern regarding the potential loss of reporting and the impact this has on government’s ability to provide effective oversight of the care and protection system and gain insight into target populations.

NZCCSS supports a focus on evidence-based decision-making and investment, guided by measurable outcomes and robust data. Section 7AA has legislated increased measures and reporting about tamariki Māori who come to Oranga Tamariki’s attention, and accountability for how government is progressing in its efforts to reduce disparities for this population. We are concerned that a repeal of section 7AA will diminish the government’s efforts to continue these measures and reporting, resulting in less insight to inform decision-making about policy, resourcing, and practice. We refer to the Waitangi Tribunal report which indicates that:

Of particular concern is officials’ assessment that, without replacing the section 7AA accountability and reporting mechanisms, work to reduce inequities may slow, which could have material impact on the safety, stability, rights, needs, and long-term wellbeing of the children with whom the department interacts (p. 16).

This repeal is occurring concurrent to the loss of other initiatives measuring child wellbeing, such as the diminishing profile of the Child Poverty Reduction Unit, the loss of the Living in Aotearoa longitudinal survey, which was to provide the basis for government’s persistent child poverty measure, and the loss of funding for the Growing Up in New Zealand research.

The repeal of 7AA affects reporting of both the experience and outcomes of tamariki Māori via the annual 7AA reports, and accountability of Oranga Tamariki via the 7AA Quality Assurance Standards reporting. Yet at the same time the government is seeking to strengthen oversight of the Oranga Tamariki system. We urge government to ensure that the valuable insights delivered via section 7AA reporting are retained through alternative reporting mechanisms. A continued focus on outcomes and reporting is required to ensure that we progress in reducing disparities in child wellbeing.

12. Intergenerational implications of policy swings

NZCCSS advocates for strong stewardship of our nation, led by a government that takes an intergenerational view of wellbeing. For this to be achieved, we must consider cross-party, enduring commitments and resist the urge to swing between polarised policy approaches to the detriment of those who most require our protection and support.

The repeal of section 7AA contradicts the original intent in establishing Oranga Tamariki, which included putting “a high degree of specific focus on improving outcomes for Maori children and young people” (State Services Commission, 2016, p.3).

Oranga Tamariki was established with a very bold and challenging vision – creating a child-centred care and protection agency and system change to improve outcomes for all of our children and address the particular issues facing tamariki Māori. (Section 7AA report, 2020, p.4).

As well as diminishing accountability for outcomes relating to tamariki Māori, the repeal of section 7AA represents a swing away from Oranga Tamariki’s original focus on prevention and reducing the necessity for tamariki to enter state care. Our membership is deeply concerned by the growing lack of responsiveness from Oranga Tamariki in recent years and the increasingly high threshold for engagement to occur. This is mirrored in a report from Otago University which reflects “community professionals losing faith in reporting as a mechanism to keep children safe, and opportunities for collaborative practice are lost” (Radio New Zealand, 2024).

We cannot claim to be focused on improving outcomes for children but continue to reduce responsiveness of the system to crisis-only intervention, nor should we backtrack mechanisms that support collaborative approaches to prevention.

13. Adequate investment in supporting families to care for children effectively is essential for the success of family preservation approaches.

The Oranga Tamariki Act preferences a family preservation approach to care and protection, recognising the importance of children remaining with parents or family/whānau wherever possible, and maintaining these connections when remaining in their care is not appropriate. It provides for early intervention so that families are supported to care for their children, reducing the likelihood of state care being required. It also provides for support for caregivers, so that when alternative care is needed, those who provide it can do so effectively.

Yet we continue to see in Oranga Tamariki a poorly resourced agency that is struggling to do justice to these objectives. As discussed above, our members are deeply concerned about the lack of responsiveness, inconsistency in decision making and high staff turnover we experience when interacting with Oranga Tamariki. We are equally alarmed by the recent reduction in Oranga Tamariki funding for community services and the inevitable cuts to frontline services that will result. These cuts are likely to impact the provision of services such as 24/7 Teen Parent Units, counselling, foster care provision, wrap-around response, intensive parenting support and others.

Improving outcomes for tamariki is reliant on a system that provides a continuum of support to parents and caregivers. A failure to adequately resource this limits our ability to make any progress in reducing both overall demand for care and protection services, and disparities within that demand. This challenge will only be exacerbated by a return to focusing on crisis-level intervention rather than prevention.

We also highlight concerns regarding how investment occurs within the care and protection context under a social investment approach:

This is an area where the social investment paradigm could become unstuck. It assumes that by providing family services of some kind or another, problems can be ‘fixed’ and that we will know those problems are fixed when families no longer need help (or no longer impose a future cost on the state). The implicit assumption here is that independence from the state is always a good thing – but this is at odds with the many families who require ongoing support to parent, partly because parenting is tough and everyone needs support at some point to do it, and because some family difficulties are complex, chronic, or not amenable to change. By assuming that there is ‘no legitimate dependence’ on the state, the social investment paradigm could generate mismatches between the services offered and the needs of recipients. It also tacitly judges target families as ‘failures’ when ongoing support is required and may in reality not align with being ‘child centred’ where to be so may result in more cost to the state. (Keddell, 2017, p 47)

We refer to the overarching recommendation within the Te Kahu Aroha report (2021) which speaks to the need for adequate and equitable investment:

Therefore, our overarching recommendation under our first term of reference is that collective Māori and community authority to lead prevention of harm to tamariki and whānau must be strengthened. This should be supported by changing how we invest, so that there is adequate and equitable funding secured for the long-term for Māori and community groups to lead prevention, and in order to provide more benefit for all New Zealanders (p.28).

We advocate for increased and ongoing investment in preventative services and resourcing of Māori and community organisations to effectively deliver services to meet demand in their context.

14. Assumptions about harm to children may fail to adequately recognise where harm continues to occur

The Cabinet Paper and justification for this repeal fails to adequately acknowledge the reality of harm experienced by children within our care and protection system, and the assumptions we may hold regarding the care of children. We cannot pretend that removing children from one unsafe setting means they will automatically be safe from harm.

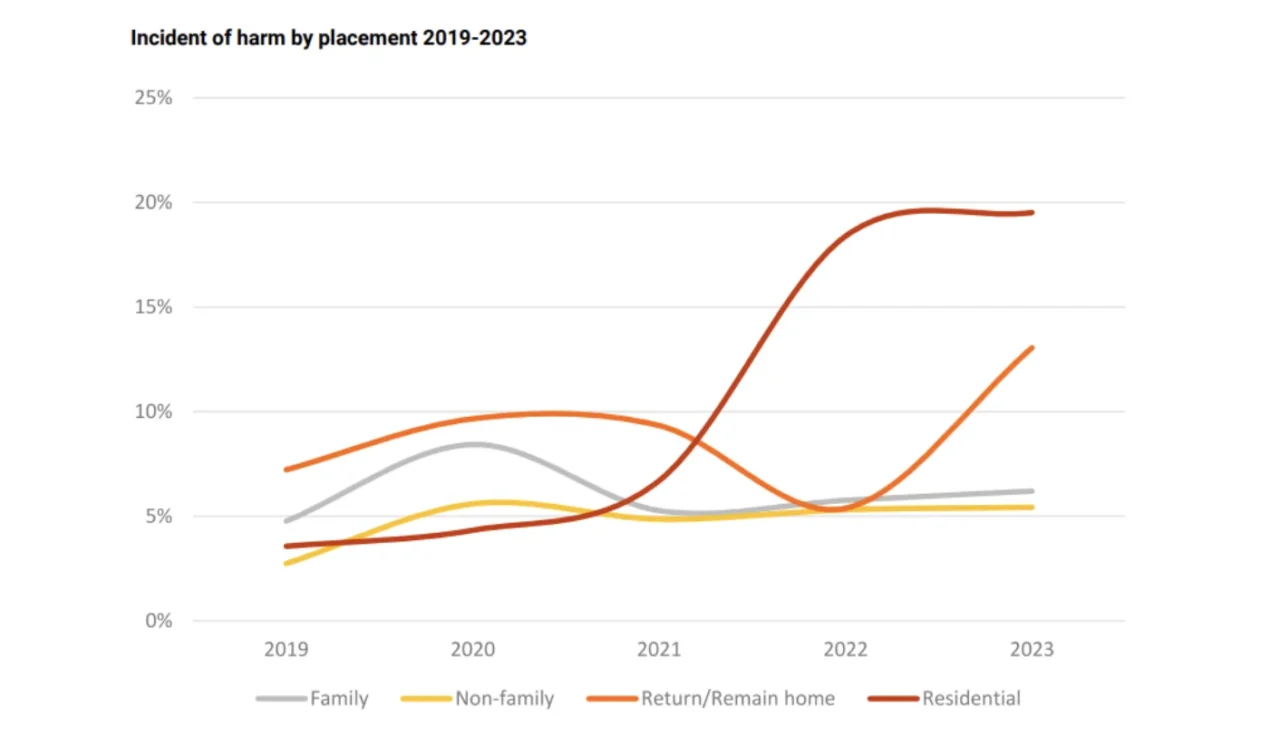

Oranga Tamariki Safety of Children in Care reports indicate that while children are more likely to experience harm in return home placements, the likelihood of experiencing harm when placed within whānau care is at a similar level to that experienced by children in non-whānau care. Children are most likely to experience harm within residential care settings.

Source: Oranga Tamariki, 2023, Safety of Children in Care Report

In failing to provide a robust evidence base for this repeal, the government has also failed to conduct a comprehensive analysis of where and how harm occurs, and the likelihood that children will continue to experience harm if removed from their home setting, as opposed to increasing support targeted at keeping children safe within their home or whānau context.

Likewise when it comes to the stability of placements for children we must recognise that removal from a parent’s care does not necessarily equate to children then being in a stable placement. Safety of Children in Care reports highlight that even young children experience multiple placements.

Crittenden & Spieker (2023) in their review of literature relating to child separation in a range of settings, identify another assumption that is relevant to this repeal, finding that “Possibly the most striking finding of our review is that separation has largely been overlooked as a serious threat to children’s well-being. On the contrary is it widely used to protect children.” (p.1)

In our discourse around how to improve the safety and stability of tamariki, we must not idealise state care and fail to recognise the impact that removal from a parent’s care and experiences within the care and protection system have on a child’s wellbeing

- Greater clarity is needed regarding the intent of the repeal, and implications of the repeal on practice and resourcing.

NZCCSS suggests that the Cabinet Paper fails to provide clarity of, and evidence to support, the specific problems the Minister seeks to address through this repeal. We seek clarification of the specific outcomes the Minister seeks to change, detailed information about the current state of these outcomes and greater definition of what success would look like following a repeal.

The poorly-defined nature of this proposed repeal in how it has been presented to date means that it is unclear exactly how success would be defined, monitored and measured if the repeal were to proceed, and how children would be better off as a result of this change.

We also seek greater clarity regarding how a repeal of section 7AA will be implemented within Oranga Tamariki and the wider care and protection system. We are specifically interested in how the repeal will impact practice guidelines and how kaimahi will be supported to implement this change.

We observe that there has been no formal consultation through the regulatory process to date with children or young people and seek clarification of how the repeal and subsequent shift in practice will be communicated to children and young people.

We observe that section 7AA initiated the establishment of specialist Māori Kairaranga-a-whānau roles, which have contributed to a range of positive outcomes detailed in the Regulatory Impact Statement. We query whether a repeal of section 7AA will impact the retention of these roles.

Tūtohutanga | Recommendations

We make the following recommendations regarding the repeal of section 7AA:

1. That section 7AA be retained in the Oranga Tamariki Act.

2. That the government ensure legislative change does not infringe upon children’s rights under te Tiriti o Waitangi, the UNCRC and UNDRIP.

3. That te Tiriti be upheld in any changes to legislative or policy.

4. That issues of practice be addressed across the system.

5. That legislative change be guided by evidence rather than ideology.

6. That relevant review mechanisms and evidence inform the timing of legislative change.

7. That any legislative change focus on strengthening the paramountcy principle, rather than repealing 7AA.

8. That the government focuses on increasing consistency of decision-making regarding children’s best interests.

9. That the mana tamaiti principles be recognised as intrinsic to the wellbeing and best interests of tamariki Māori.

10. That efforts be made to maintain the trust that has been established between the government and Māori as a result of the provisions in section 7AA.

11. That the legislative basis for strategic partnerships with iwi/Māori be retained.

12. That the provisions within section 7AA for accountability of the Oranga Tamariki system and reporting on outcomes for tamariki Māori be retained.

13. That the government resists policy swings that impact our ability to make long-term change.

14. That the government invest adequately in supporting family preservation approaches to care and protection.

15. That robust analysis of legislative change be undertaken to challenge any underlying assumptions regarding children’s safety.

16. That greater clarification of the proposed repeal and implications for practice be provided.

Tohutoro kua tohua | Selected references

Crittenden, PM. & Spieker, S. (2023). The Effects of Separation from Parents on Children. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.1002940

Keddell, E. (June 2017). The Child Youth and Family Review: A Commentary on Prevention. Auckland: The Policy Observatory. https://thepolicyobservatory.aut.ac.nz

Keddell, E. & Wilkins, D. (2022). The relationship between perceptions of risk, child welfare experience and country of origin: a comparative study of student social workers in Wales and Aotearoa New Zealand. http://dx.doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.19833.13927

Ministerial Advisory Committee on a Māori Perspective for the Ministry of Social Development (1988). Te Pūao-te-Ata-Tū. https://www.msd.govt.nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/archive/1988-puaoteatatu.pdf

Oranga Tamariki (2020). Section 7AA Report 2020. https://www.orangatamariki.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/About-us/Performance-and-monitoring/Section-7AA/S7AA-Improving-outcomes-for-tamariki-Maori.pdf

Oranga Tamariki (2023). Section 7AA Report 2023. https://www.orangatamariki.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/About-us/Performance-and-monitoring/Section-7AA/7AA-Web_V5.pdf

Oranga Tamariki (2023). Safety of Children in Care Report. https://www.orangatamariki.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/About-us/Performance-and-monitoring/safety-of-children-in-care/2022-23/J000093_SOCIC-Report-2023_v4.pdf

Oranga Tamariki Ministerial Advisory Board (2021). Hipokingia ki te Kahu Aroha, Hipokingia ki te katoa (Te Kahu Aroha). https://www.beehive.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2021-09/SWRB082-OT-Report-FA-ENG-WEB.PDF

Radio New Zealand (2024, May 7). Community groups feel ignored by Oranga Tamariki – study. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/516149/community-groups-feel-ignored-by-oranga-tamariki-study

State Services Commission (2016). Regulatory Impact Statement – organisational form to support new operating model for vulnerable children. PFA SECTION 04(D) – 2006/07 SOI GUIDANCE (msd.govt.nz)

Te Puna Rangahau o te Wai Ariki | Aotearoa New Zealand Centre for Indigenous Peoples and the Law (2022). Determining the best interests of tamariki Māori in need of care and protection. University of Auckland. https://www.auckland.ac.nz/assets/law/Documents/2023/TeWaiAriki/FINAL%20VERSION_Determining%20the%20Best%20Interests%20of%20Tamariki%20M%C4%81ori%20in%20Need%20of%20Care%20and%20Protection_December%202022.pdf

Waitangi Tribunal (2024). The Oranga Tamariki (Section 7AA) Urgent Inquiry Report. https://forms.justice.govt.nz/search/Documents/WT/wt_DOC_212767746/Oranga%20Tamariki%20Urgent%20W.pdf

Williams, T., Ruru, J., Irwin-Easthope, H., Quince, K., & Gifford, H. Care and protection of tamariki Māori in the family court system. Te Arotahi. May 2019. Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga | New Zealand’s Māori Centre of Research Excellence. teArotahi_19-0501 Ruru.pdf (maramatanga.ac.nz)

Ingoa whakapā | Contact Name

Nikki Hurst