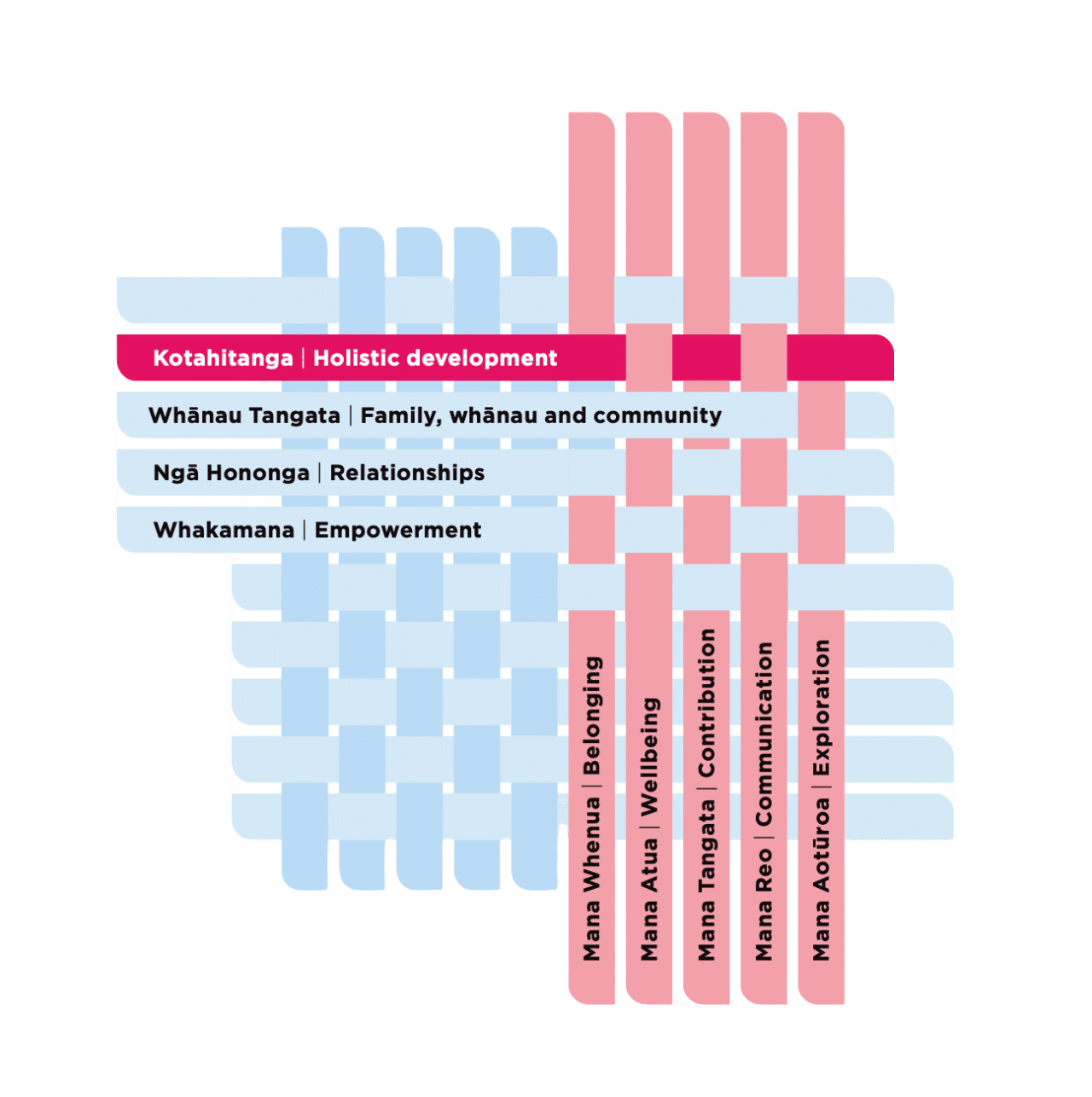

A good understanding of child development is needed to support children. Generally, a holistic lens is most helpful, being comprised of physical, emotional, social, cognitive and spiritual domains. This recognises two key things: firstly, that these areas are all interconnected, and secondly, that development does not necessarily follow a straight line at all times. Te Whāriki highlights the essential nature of the spiritual dimension for Māori, in that it “connects the other dimensions across time and space” (Ministry of Education, 2017, p.19).

“Although the preschool years establish the base for future development, experiences in middle childhood can sustain, magnify, or reverse the advantages or disadvantages that children acquire in the preschool years. At the same time, middle childhood is a pathway to adolescence, setting trajectories that are not easily changed later.”

Huston & Ripke, 2006, p.2

Almost 40 years ago a major review into middle childhood took place in the United States, led by a panel established by the Committee on Child Development Research and Public Policy at the National Academy of Sciences. Researchers concluded:

Middle childhood behaviour and performance have repeatedly been found to predict adolescent and adult status, including social and personal dysfunction, more reliably than do early childhood indicators, and this predictiveness increases over the years from 6 to 12. (Collins, 1984)

According to Huston & Ripke (2006), this finding “contradicted two widespread notions” which we believe a lot of people continue to think today: “that a child’s future is shaped in early childhood and that little of interest happens in middle childhood compared with “coming of age” in adolescence. (p.1)”

The value of understanding and supporting children’s holistic development during middle childhood is crucial. But a consistent lack of attention on this age stage means that understanding our five to 12-year olds now requires a weaving together of traditional and emerging knowledge.

Greater importance must be placed on developing good understanding specific to this age stage and our context of Aotearoa. This understanding must be from good evidence, and local and current research. And as this develops, the knowledge should be shared with children, their families, and the workforces they encounter in the process of their development

Mana Whenua | Belonging

Within Te Whāriki, Mana Whenua (belonging) is the importance of children feeling a sense of place and their links to family and the wider world – their turangawaewae. Children’s sense of identity is forming during middle childhood as their awareness and understanding of cultural and social values develops. They are also shaping their own views about society as their ability to think critically grows.

Mana Whenua underpins holistic development and is a protective factor for children’s mental wellbeing (Fletcher et al., 2023).

The quote below makes the point that belonging, connection and attachment continue to matter as children move into middle childhood. Belonging matters for physical and neurological development and is often seen in social and emotional behaviours. Our ability to create environments that foster belonging are also supported by the prioritisation of Te Ao Māori principles.

“Children’s brains hunger for social connection and the feeling of belonging. When children do not sense that they belong and when they struggle to reconcile irregularities in their environments, their brains are malnourished and fail to develop in healthy ways”

Annan, 2022, p.185

Te Ao Māori Perspective

Within Te Ao Māori, child development is underpinned by the following principles:

Mana and Mana Tamaiti (Tamariki)

In Te Ao Māori, tamariki are considered taonga – a precious gift connecting past, present and future generations. Early European accounts of Māori whānau show that tamariki were treated with adoration and indulgence, in contrast with the more reserved European approach to child-rearing at that time (Salmond, 2017).

According to Mana Mokopuna (Children & Young People’s Commission) (2017) mana tamaiti refers to “the intrinsic value and inherent dignity derived from a child’s or young person’s whakapapa genealogy) and their belonging to a whānau, hapū, iwi, or family group, in accordance with tikanga Māori or its equivalent in the culture of the child or young person”. In short, that children have their own value, resulting from their whakapapa and the communities in which they belong.

Mana builds on the concept of tamariki as taonga who possess power, influence, and prestige (Rameka, 2015).

Whakapapa

“He Tupuna he mokopuna. Mā wai i whakakī i ngā whawharua o ngā mātua Tupuna? Mā ā tātou mokopuna! he mokopuna he Tupuna”

This whakataukī draws us to the essence of the whakapapa relationship between generations. It asserts that we are all mokopuna and we are all tupuna. The mokopuna will in future generations take the place of the tupuna. All grandchildren in time become grandparents. Each generation links through whakapapa to each other and we are a reflection and continuance of our ancestral lines” (Cameron et al., 2013, p.4).

Whakapapa is the genealogical link that connects tamariki or mokopuna (grandchildren) to tupuna (ancestors), whānau and whenua (land). Through these links tamariki inherit traits such as tapu (sacredness), mana (status/power), mauri (life force) and wairua (spirit). These provide mokopuna with their sense of belonging, identity, and contribution within their community. Knowing and maintaining connection to these links are considered essential for the wellbeing of tamariki. (Greensill et al., 2022), (Rameka, 2015).

Whānau

Responsibility for the wellbeing, nurturing and development of tamariki is shared by the child’s community collectively.

Grandparents and wider whānau members play an active role in the care of mokopuna and their holistic development, including the sharing of knowledge and tikanga.

In Te Ao Māori, tamariki wellbeing can’t be viewed independently of the wellbeing of their wider whānau and community.

“…raising a child is not an individual endeavour, but rather a job for the whole community…any consideration of wellbeing for tamariki Māori must necessarily consider the role of whānau and importantly the wellbeing of the whānau collective”

Pihama et al, 2019, p.5

Cognitive Development

Middle childhood is considered a ‘sensitive period’ of brain development, where experiences children have during this period continue to have a strong impact on their development. During sensitive periods of brain development experiences impact how information is processed or represented within the brain. Also, children’s behaviour and beliefs about themselves and the world come from the way their brain adapts to this information. (Knudsen, 2004) (Mah & Ford-Jones, 2012).

During middle childhood connections within the brain continue to develop through neuron generation, myelination, and synaptic pruning. Neurons are nerve cells that convey messages

throughout a child’s body. Myelination is where a sheath forms around nerve fibres, increasing the speed and efficiency of nerve impulses. Synaptic pruning also increases the efficiency of the

brain by eliminating unused connections. (Johnson et al., 2009)

Specific developments across this age include maturing of the corpus callosum, the connection between the two hemispheres (sides) of the brain. This enhances children’s ability to carry out

tasks that use both left and right brain hemispheres. Myelination also occurs in the areas of the brain connecting sensory, motor and intellectual functioning. This increases the information processing speed within the brain and children’s reaction times (Paris et al., 2021; Pye et al., 2022).

Brain development is influenced by the experiences children have during early and middle childhood. Children are shaped by learning opportunities, relationships that nurture them, friendships they form, interactions with peers, the extent to which they feel safe, the social and cultural context they exist within and the way in which they establish meaning from their experiences.

“Although the brain has various innate structures that carry out particular functions, such as moving, speaking and reasoning, the precise nature of connections between the parts is primarily shaped by experience”.

Annan, 2022, p.43

Aspects of children’s development during middle childhood include:

Executive Function

Developments in the prefrontal cortex enable the advancement of executive function during middle childhood.

Specific areas of advancement during middle childhood include:

| Aspect of executive function | Example |

|---|---|

| Working memory | Remembering directions, instructions, someone’s name, or thinking up the answer to a question asked by the teacher. |

| Organisation | Being able to arrange information or things in a systematic way, this might look like a child keeping their room tidy, or being able to organise their thoughts into a story, being able to sort items into categories or groups |

| Response inhibition | Ignoring a distraction or stopping a thought or action based on context |

| Emotional control | Regulating emotions based on context, developing strategies to cope with emotional stress |

| Task initiation | Beginning a chore or piece of schoolwork, motivating oneself to begin something difficult or unpleasant |

| Mental flexibility | The ability to change from one task to another, or adapt to a change in plans, problem-solving |

5-7 Shift

The initial years of middle childhood have been referred to as the ‘5-7-Year Shift’ or the ‘age of reason’, marking the transition that occurs as children move from early childhood to middle childhood. At age seven, children are typically more able to think rationally and self-regulate sufficiently to engage in formal academic learning, or in some parts of the world, the workforce

(Arnett et al., 2020; McAdams, 2015).

Early Adolescence

Early adolescence (around ages 10-12) sees children’s abilities in planning,

logical thinking and decision-making. At this age children are better able to control impulses or inhibit behaviour, however the part of the brain that controls these functions does not fully mature until adulthood. (Tooley et al., 2022) (Fraser-Thill, 2022).

Social Awareness

“Social cognition is the way in which people process, remember, and use information in social contexts to explain and predict their own behaviour and that of others.”

Bulgarelli & Molina, 2016

As the prefrontal cortex develops, children become better able to navigate their social world. This is called social cognition. They develop the ability to recognise and understand social signals and the expected response to those signals. This function also relates to motivation and reward, as children learn to understand how their behaviour may be received and then use this information to respond to their context. (Uytun, 2018)

Emotional recognition is another key aspect of social cognition that develops during middle childhood. Emotional recognition enables children to identify and recognise other people’s emotions based on body language such as facial expressions and vocal cues. Current thinking in this area has developed from traditional understandings of attachment theory. In particular, how facial and body cues can help us navigate our social worlds. Emotional recognition is considered to be critical to children’s social development and emotional regulation during middle

childhood as children learn what behaviours and expressions of emotion are socially acceptable, and as friendships become more complex and take on greater importance in children’s lives (Garcia & Tully, 2020).

During middle childhood children grow in their ability to consider things from another person’s perspective. A key aspect of this is the development of theory of mind. Theory of mind is how we understand other people’s mental state in relation to ourselves, and the world around us. Theory of mind grows during middle childhood by developments in the brain (e.g. language, executive function) and environmental factors (family, cultural and educational context) (Wang, Devine, Wong & Hughes, 2016).

Friendship

Friendships are a focus for children as they become more independent. They have typically moved from playing alongside each other to cooperative play with other children. This leads to increased importance being placed on friendship with more of an awareness of similarities and differences.

Relationships and friendships tend to be a place for children to test developing interpersonal skills, as well as learning about their own personality and preferences. Children develop communication and negotiation skills (taking turns, giving/receiving, sharing, compromise, conflict resolution), the ability to initiate interactions or play with others, and greater awareness of others’ feelings and needs. It is common for children to have challenges with establishing, maintaining, and changing friendships and they may want support to navigate these experiences and the feelings associated with this.

During middle childhood children begin to notice social and peer-group norms. They may test out changing their behaviour to gain or keep friends. Children’s play becomes more gendered –

they are more likely to play with children of the same gender and more likely to reflect gendered norms in their play such as role-playing stereotypical gender roles.

“Just being around other children, however, is not enough. The development of friendships is essential, as children learn and play more competently in the rapport created with friends rather than when they are dealing with the social challenges of interacting with casual acquaintances or unfamiliar peers.”

National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2004, p.2

Friendship is a primary motivator for children’s school attendance, with 80% of students in a survey conducted by the Education Review Office (2022) saying that seeing and spending time with friends is a reason for attending school.

Bullying, behaviour that involves a misuse of power, is persistent and causes deliberate harm to another person, may become an issue for children in middle childhood. See more about bullying in our Ngā Hononga section.

Two key hormonal developments that occur during middle childhood are:

Adrenarche

Between six and eight years of age, children’s bodies enter a stage called Adrenarche.

The adrenal glands (located above the kidneys) begin to increase production of androgens – hormones that affect brain functioning. These hormones impact children psychologically and emotionally but this change is not typically physically obvious.

Children may have difficulty managing their emotions and behaviour during adrenarche, becoming more tearful, angry, moody, and argumentative. Adrenarche is thought to occur at least two years before puberty. (Ball, 2022) (Del Giudice, 2018).

Early Adolescence

Early adolescence begins with the onset of puberty which begins between the ages of 8-13 for girls, and 9-14 for boys (Marks et. al, 2023).

Children tend to move from black and white (concrete) thinking towards more abstract thought during this period. They become self-focused and self-conscious as they experience their bodies

are physically developing and are more aware how they fit in with others. Early adolescence sees children growing in independence and seeking greater privacy. Peer relationships become more of a priority in this period, as children shift away from family as their primary influence. While cognitive functions are well-developed in children at this stage, they may continue to find it difficult to regulate their emotions and may engage in more risky behaviour (Lang et al.,2022).

Physical changes that occur during puberty are discussed in the tables on the bottom of this page.

— Find out more about Young People’s Experiences of Puberty

Social & Emotional Developmental Milestones

The following are general developmental milestones that often happen at the specified ages. In reality, children will reach these milestones at a variety of ages. While developmental milestone guides for early childhood are prevalent, this information is less accessible for middle childhood in Aotearoa.

These milestones have been identified through a range of sources which can be found in the bibliography

Models of Social and Emotional Development

Models relating to children’s social and emotional development during middle childhood include:

Mātauranga Oranga

A Te Tiriti-based, ako framework for social emotional wellbeing

This model has been developed by Fickel et. al (2023) to meet the need for approaches to Social Emotional Learning that incorporate Te Ao Māori perspectives on wellbeing. The process of consultation with kaiako, tamariki and whānau towards shaping this framework identified that relationships, belonging and feeling connected, and identity and sense of self, were all central to wellbeing.

ibid, p.9

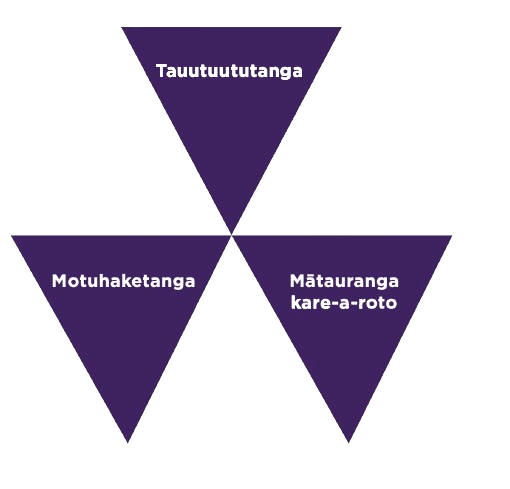

Ako Torowhānui

The three triangles within the Mātauranga Oranga framework represent Ako Torowhānui – a “culturally responsive and sustaining construct of Social Emotional Learning” (p. 9). Communication, understanding emotions and emotional states, and normalising and reframing social-emotional experiences, were found to be important attributes of social emotional learning and these are reflected in the following Māori concepts:

- Tauutuututanga: this concept represents the importance of reciprocal communication which is underpinned by respect and empathy.

- Motuhaketanga: this concept reflects the “interconnection of autonomy, independence and self-guidance”

- Mātauranga kare-a-roto: this concept reflects the understanding of emotions and emotional states that is needed to enable positive self reflection and relationships.

Find out more about Mātauranga Oranga

Social and Emotional Competencies

The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) model of social and emotional competencies is one of the most prevalent models referred to in an educational context.

The CASEL framework comprises five competencies relating to social and emotional learning (SEL):

- SELF-AWARENESS: The abilities to understand one’s own emotions, thoughts, and values and how they influence behaviour across contexts.

- SELF-MANAGEMENT: The abilities to manage one’s emotions, thoughts, and behaviours effectively in different situations and to achieve goals and aspirations.

- SOCIAL AWARENESS: The abilities to understand the perspectives of and empathize with others, including those from diverse backgrounds, cultures, & contexts.

- RELATIONSHIP SKILLS: The abilities to establish and maintain healthy and supportive relationships and to effectively navigate settings with diverse individuals and groups.

- RESPONSIBLE DECISION-MAKING: The abilities to make caring and constructive choices about personal behaviour and social interactions across diverse situations.

(Source CASEL, 2020, p.2)

The CASEL approach seeks to embed these competencies into settings children engage in through a partnership approach between the classroom, school, home, and the community.

“SEL is the process through which all young people and adults acquire and apply the knowledge, skills, and attitudes to develop healthy identities, manage emotions and achieve personal and collective goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain supportive relationships, and make responsible and caring decisions”.

CASEL, 2020

The CASEL model has been used in many educational contexts to guide the teaching and assessment of SEL. View how these competencies relate to the New Zealand Curriculum Key Competencies by clicking here.

Find out more about CASEL by clicking here

Click on this link to read the article by Denston et. al (2022) explores the relationship between social emotional learning approaches such as the CASEL model and culture, noting that most approaches to social emotional learning are based on universalistic concepts of wellbeing. This research finds that in an Aotearoa context, “culture, language, and identity are fundamental to understandings of wellbeing in students….these elements can contribute to developing relationships among students, teachers, and whānau, in a mutually reinforcing manner“(p.17).

This work supports the need for concepts such as the Mātauranga Oranga framework above, which has been shaped by a Te Ao Māori understanding of wellbeing.

7 Dimensions: Children’s Emotional Wellbeing

– Jean Annan, 2022

Jean Annan is an Aotearoa-based psychologist who established the 7 Dimensions: Children’s Emotional Wellbeing framework.

This framework brings together knowledge about child development and neuroscience to identify seven ‘dimensions’ of children’s wellbeing framed around three key themes of safety,

experience and meaning. Annan’s framework suggests that children seek the answer to seven fundamental questions as the develop, as outlined in the table below. While Annan’s book

primarily explores use of this framework in educational settings, her work is a useful model for anyone caring for or working alongside children.

(Annan, 2023, p.11-16)

Find out more about 7 Dimensions: Children’s Emotional Wellbeing

Mana Atua | Wellbeing

“Middle childhood is an important period in children’s development-those who are thriving in this stage are well set up for long-term wellbeing”

(Carr, 2011)

Mana Atua | Wellbeing goals for children are that their health is promoted, their emotional wellbeing nurtured, and that they are kept safe from harm. This happens when wellbeing frameworks are holistic, current, and have good understanding of children’s physical, social, cognitive, and spiritual development and health.

Holistic Models of Development

Holistic theories of development tend to include physical, social/emotional, relational, and cognitive aspects of a person’s development, and increasingly also explore how their environment shapes their development. Many cultures will also include spiritual development into a holistic framework of development.

The following are some examples of holistic models of development that are commonly applied in an Aotearoa context. It is important to note that these models are not specifically children’s models and are applied across the lifespan:

Te Whare Tapa Whā

Probably best known, and most frequently used, Tā Mason Durie developed Whare Tapa Wha in 1984.

It is a model of four taha or walls that need to be balanced equally for wellbeing to be achieved. These taha are whānau (family health), tinana (physical health), hinengaro (mental health) and wairua (spiritual health).

— You can read more about this model here

— Examples of how this model can be used with children can be found below:

- Using Te Whare Tapa Whā for learning about wellbeing: activities for year 1-8 ākonga. Click HERE

- Sparklers ‘Fill my… whare tapa whā’. Click HERE

Te Wheke

This is a Māori model of wellbeing developed by Rangimārie Rose Pere in 1997.

Through the framing of an octopus’s eight tentacles, Te Wheke represents eight interrelated aspects of life that must be supported to maintain wellbeing: whānau (family), waiora (wellbeing for the individual and family), wairuatanga (spirtuality), hinengaro (mind), taha tinana (physical body), whanaungatanga (extended family), mauri (life force) mana ake (identity), hā a koro

ma, a kui ma (breath of life from forebearers), whatumanawa (the open and healthy expression of emotion).

— You can read more about this model here

Fonofale

Fonofale is a Samoan model of health that encompasses components viewed as essential to wellbeing.

Framed around the model of a fale (house), Fonofale positions cultural beliefs and values as the roof providing shelter, and family as the foundation of wellbeing. The Fonofale model integrates spiritual, physical and mental dimensions of health as well as a fourth dimension named ‘other’ which incorporates factors that might influence health such as sexual orientation and socioeconomic or employment status. These dimensions connect the roof and the foundation together. (Ministry of Health, 2008)

— An example of how this model can be used with children can be found here: https://sparklers.org.nz/activities/my-fale-house/

The Fonua Model

This is a Tongan model of wellbeing developed by Sione Tu’itahi in 2009.

This model comprises five interdependent dimensions of life which must all be supported in order to maintain harmony and wellbeing:

- Atakai (environment)/Mamani (global)

- Kainga (community)/fonua (national)

- Sino (physical)/kolo (local)

- Atamai (mental)/famili (family)

- Laumalie (spiritual)/taautaha (individual).

This model also recognises four phases of development: Kumi Fonua/exploratory, Langa Fonua/formative, Tauhi Fonua/ maintenance, Tufunga Fonua/reformation. (Health Promotion Forum of New Zealand, 2023)

— Read more about the Fonua Model here

There are many other holistic models of health that have been developed to represent a particular culture and what it values. Generally, these include physical, mental, social/emotional, and familial or community wellbeing. Many also include aspects of faith or personhood.

None seem to have been developed specifically for tamariki in their middle years.

Physical Development in Middle Childhood

The following are general developmental milestones that often happen at the specified ages. In reality, children will reach these milestones at a variety of ages. While developmental milestone guides for early childhood are prevalent, this information is less accessible for middle childhood.

Initiatives focused on encouraging and enabling children’s active movement include:

Healthy Active Learning

Healthy Active Learning is a joint initiative between the Ministry of Health, Ministry of Education and Sport NZ, which aims to support schools and kura to create environments that support and promote play, sport, and physical activity.

Over 800 schools and kura are engaged with the Health Active Learning initiative, with a focus on decile 1-4 schools (according to the previous Decile system). This evaluation of Healthy Active Learning shows that participating schools have increased the value placed on physical activity within the school environment and improved teaching practice in relation to physical activity

— To find out more about Healthy Active Learning, click HERE