After an intense 14-month period the final report of the Productivity Commission’s top-down inquiry into social sector services – More Effective Social Services – was released on 15 September to a muted response.

The most prominent coverage in this first week was probably the DominionPost editorial on 18 September (click on image to read):

The Productivity Commission, established five years ago, has developed a very layered and consciously designed approach to its process – from issues paper, to draft, to final copy.

The Productivity Commission, established five years ago, has developed a very layered and consciously designed approach to its process – from issues paper, to draft, to final copy.

Including all of its appendices and associated documents, this latest report – containing 89 Findings and 61 Recommendations – topped 600 pages.

Introducing the report, Commission chair Murray Sherwin, wrote that the report’s authors had concluded “that it was not enough to just make the current system work better”, and set out the report’s two main drivers:

- System-wide improvement can be achieved and should be pursued [through system architecture].

- New Zealand needs better ways to join up services for those with multiple, complex needs [through lifting the game on commissioning social services].

While the final report repackaged or reconfigured some elements, introduced some new diagrams and added a few surprises not contained in the draft released in April, it was another mixed bag.

A new construct

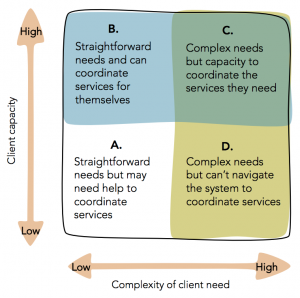

The key diagram used to set the scene for the final report was an artificial construct used to represent characteristics of clients of the social services system. This was accompanied by an assertion that “to maximise their effectiveness, social services should be arranged differently to match the needs of people in different quadrants” (p3, full report).

It is a fair call by the Commission to identify a “failure to treat deep disadvantage” as the main weakness of the current system. Particularly if that “deep disadvantage” encompasses evidence of inequality and poverty.

One of the things this construct didn’t accommodate was the idea that people might move between ‘boxes’ at different times in their lives, but rather latched on to the concept that Quadrant D is where all of New Zealand’s “highest cost clients of the social services system” could be located.

The unexplained estimate of 10,000 was then used for the number of clients in that too-hard box, but the report unfortunately didn’t drive through to a clear and meaningful focus on how to address opportunities for early intervention to avoid the escalation of problems with this group, let alone put this into a community-based setting. That was a missed opportunity.

Devolved approaches

What it did do, in the biggest change between the draft and final report, was to hammer the idea of “greater use of client-directed and other devolved approaches”, to be complemented with other measures such as national standards, regulation and data collection that might, at the same time, involve “some centralisation”.

In terms of a ‘language shift’ mentions of devolution went from 86 in the draft report to more than 260 in the final report.

The definition used – as a counterpoint to top-down control – was that devolution “transfers substantial decision-making powers and responsibilities to autonomous or semi-autonomous organisations with separate governance”.

Examples given where decision making has been devolved with varying levels of independence were DHBs, Pharmac, Whānau Ora and the Te Hiku Social Accord.

On the surface devolution that encourages flexible adaptation to client needs and local circumstances sounds attractive and is an apt description really of what NZCCSS members already do, as hinted at by this encouraging statement in the report’s section on devolution:

More use should be made of the abilities, knowledge and capabilities of the many providers and community organisations that know and work with such people

Commissioning at the centre

Having already stated the view that “there are limits to gains that government can achieve by improving the contracting-out model” and that contracting out is overused, the report next champions a framework of commissioning, and positions effective commissioning as being “fundamental to well-functioning social services”.

This isn’t to say that contracting out is going to disappear. As noted by the Commission – and as we know full well in our sector – considerable effort is being applied to streamline contracting, and the emphasis in this report that there should be a standard duration of three years to social services contracts is welcome.

What this report pushes for is to put development of the capability for contracting out alongside improved capability for commissioning. Whether this would effectively create two playing fields, and what would be done to ensure they remain level playing fields isn’t made clear.

A commissioning framework is something that the Commission states requires a wider range of skills and capabilities “than suggested by the more commonly used term procurement”, and a strong call is made in this report for the Government to “appoint a lead agency to promote better commissioning of social services”, to include guidance and training.

Examples given of organisations that commission social services include MSD, the Ministry of Health, DHBs and Whānau Ora.

All of this is again scene setting for pushing out the case for having an array of service models for delivering social services, and weaving in the point that each system architecture or service model will display different strengths and weaknesses in promoting learning and innovation – to be used as a defacto basis for selecting winners and discarding losers.

The misleading perception that there is a lack of innovation in social services is both persistent and pernicious. It is used constantly to underpin the Commission’s thinking and to shape the system design it is promoting.

When push comes to shove its sharpest explicit criticism, supposedly not directed at the state sector, is that innovation in social services is “often small-scale, local, dependent on a few committed individuals and incremental”.

Clear preferences emerge

It is only as this report reaches its business end that the clear preferences it is driving towards begin to emerge.

In terms of service models it singles out managed markets, shared goals, voucher models, and client-directed-budget (CDB) models – specifically recommending that this prospective CDB model be trialed for home-based support of older people, respite services and drug and rehabilitation services, allied to creating “client choice whenever feasible”.

Not surprisingly the MSD’s Investment Approach (and future welfare liability emphasis) is also endorsed, to the point where the Commission would like to see it coupled to a devolved system and applied “more widely within and across different government-funded social services areas”.

In what was most probably a piece of its own risk aversion, the Commission is careful not to venture into mentions of social bonds, instead dancing around social insurance while carefully stating it is not recommending the wide extension of social insurance in New Zealand (p.16, Summary report).

In similar fashion to its critique of lack of innovation, the Commission also sets its sights on ways to achieve better integration of services – as an antidote to fragmentation and to override specialisation in social services, described willy-nilly as a barrier to efficiency and effectiveness.

A magic answer?

Focusing on Quadrant D clients, the magic answer delivered in this report to provide “an effective, integrated package of services” hinges on the role of a magic Navigator (borrowed from Whānau Ora, and suspiciously akin to a super-powered Social Worker).

This is the point in the Commission’s report where it becomes most ambiguous and vague, and yet also its most clinical.

Suddenly a lot of weight is placed on this role of Navigator, with whom a client would most likely have to be “enrolled”.

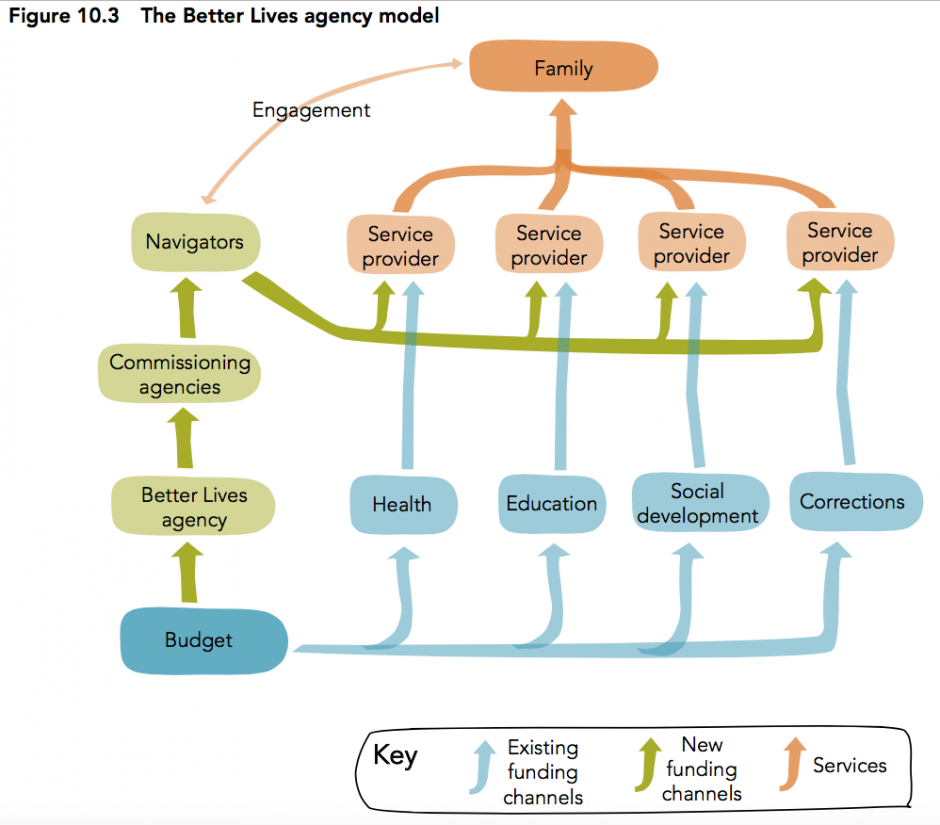

And out of nowhere the conception of this role suddenly becomes attached to two sizeable elements of Government agency restructuring: either the setting up of a Better Lives agency or widening the role of DHBs into District Health and Social Boards (DHSBs). [Question: Did anyone ask DHBs about this!?]

Either of these would then fund local Navigators who would engage with clients and have control over a budget to buy services to best meet their needs.

On the face of it this is a radical proposal, and one that this report has taken some pains to paint as a viable scenario, including a fictitious story that includes these clues as to how a Navigator would operate in an ideal world and that’s worth capturing a verbatim summary of here (p.362, full report) – with the new elements in bold:

- Denise and her children turn up late one night at Auckland City Mission in a distressed state, she with bruises and a black eye and no access to funds, the younger child clearly ill with a bad chest infection. The Mission provides the three with emergency shelter for the night.

- In the morning, the Mission takes Denise to the local service centre for the Better Lives agency (or DHSB) where she meets Sandra – her system navigator. It is Sandra’s responsibility to work with Denise to establish the services she requires and how these services are best supplied.

- Sandra listens to Denise’s story and takes her details. It will be the only time that Denise will have to provide this information as Sandra has the budget and authority to assess Denise’s situation and grant her access to the services she needs. Denise gives Sandra permission to view her personal service history from the national database. This will help Sandra better understand Denise’s circumstances and the services likely to work for her.

- Sandra arranges for Denise and her family to move into temporary housing until permanent state housing becomes available. She enrols the family with the local primary healthcare provider and makes an appointment for Denise’s youngest child to see the doctor. Sandra arranges transport to the appointment.

- Denise decides that to turn her life around she needs to be financially independent. But this will take time. Denise needs to access an unemployment benefit until she gets a job. Sandra sends the electronic paperwork to Work and Income. Because the application is coming from the Better Lives agency, it is fast tracked – Denise should have her first payment next week. To tide Denise over, Sandra gives her a payment card with enough funds for groceries for a week or so.

- Sandra and Denise shake hands and Denise leaves the Wellbeing Office. Denise gets the feeling that Sandra really understands her situation, and is someone she can trust. Denise is still worried about the future, but she can now see a pathway to a better life for her and her children.

How much will happen?

The Commission is in no doubt that the long-term reform agenda it envisages will require institutional change and leadership from the top.

This latest enabling environment would see a “small and cohesive” Ministerial Committee for Social Services Reform established along with a supporting Transition Office within the current Government’s remaining term, as well as an Advisory Board of system participants to provide the Ministerial Committee with independent expert advice on system design and transition.

The existing Social Sector Board would largely continue on and even acclerate its data-sharing and data-analysis track, with further “system stewardship” to be exerted through:

- An enhanced role for Superu (formerly the Families Commission) as the monitor and evaluator of system performance

- A rolling review of existing social services programmes against specified criteria

The Commission’s indicative timeline would see either a Better Lives agency or DHSB arrangement (or some other model) up and running in “trial locations” in 2 to 4 years time. This would constitute what the Commission calls a “new deal for the most disadvantaged New Zealanders”.

Simultaneously “client-centred-service integration initiatives” would also be initiated.

In the Terms of Reference for this Productivity Commission inquiry it is important to note that the referring Ministers – Bill English as Minister of Finance, and Dr Jonathan Coleman as Minister of State Services – advised that “consideration should be given to the characteristics of the New Zealand provider market, and how it differs from regular commercial markets and how the role of the community impacts on it”.

Between the lines of the final report – which is very clear that its purpose was not to critique the performance of specific agencies or programmes or providers – there is an implicit challenge to NFP providers to demonstrate an openness, capacity and capability to manage within new models.

There is an open invitation to be part of a step up in performance, and an invitation for leaders in our sector to contribute perceptive thinking and an active commitment to achieving change that unleashes our potential.

There is even an acknowledgement that benefits that result from well-functioning social services spill over into society.

As covered in a previous article here in July, we still have a right to be wary of the elements of this agenda that are intent on opening the door to more and more privately owned, for-profit organisations to receive an easy ride to full funding and sustainable returns without the hard yards that NFP providers are put through.

All of the Commission’s fine references to the systemic underfunding experienced by social services providers immediately start to pale if this “reform” becomes nothing more than an exercise in cutting back existing services and diverting to a “more effective” environment characterised by experimental imbalance and wider instability. The Commission is right, social services don’t suit a ‘one size fits all’ approach. On the same basis, buying into the idea that the ideal is to re-size in order to compete alongside each other to attract clients – known as competition in the market – has to be scrutinized more fully than it has been. Lest we forget without the diversity of social services and continuum of options provided by our members, their staff and volunteers, the human costs of disadvantage in New Zealand would be immeasurably higher. And where would that leave the system?

See also/ download: